2019 RAYMOND PETTIBON

When I asked Raymond Pettibon about his relationship to the classical tradition, he replied: “Without classical scholastics and philologists, I might be a hippie Jesus or blind Socrates or Homer wandering aloud in a daze.”

Pettibon is not a lone philosopher or a prophet crying in the wilderness. His practice of reinterpreting texts places him in a continuum of literary scholarship stretching from classical times through the New Criticism of the 1920s and 30s to the deconstruction of Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man. We need not be full-blown literary scholars to appreciate Pettibon’s work, but we must be willing to consider it with the same attentiveness the artist brings to his source materials.

Pettibon’s Classical Elements series is inspired by earth, air, water, fire, and aether: the five basic substances which Aristotle believed produced all others.

For his aether-themed piece, Untitled (And I rise…), he pairs an image of the 1950s claymation character Gumby with a modified quotation from a letter the nineteenth-century novelist Henry James wrote to Daniel Lathbury, then-editor of the Guardian. Lathbury had written an effusive fan letter to James after reading his novel The Reverberator, and James’s response was equally effusive: “I frankly rejoice that you obeyed the friendly impulse to write to me. That gives me the greatest pleasure—and I rise into the pure ether of refreshed ambition when I hear that acute people have found the thrill, the glow of life, as dear Matthew Arnold says, in any of my little creations.” Pettibon makes several subtle but significant changes to this epistolary text, which seem to reflect his own complex feelings about artistic influence and audience. First, James’s “acute people,” as in shrewd or astute, becomes “A CUTE PEOPLE” — like Gumby’s humanoid compatriots, perhaps, or Pettibon’s own artworld fan base. Pettibon also dumps the Matthew Arnold reference and changes the phrase “in any of my little creations” to “IN ART’S LITTLE CREATIONS.” “Art” might refer to visual art, of course, but also to Art Clokey, the creator of Gumby.

Did Pettibon find “the thrill and glow of life” in Clokey’s Gumby? Perhaps. It’s one of his favorite motifs. But Gumby is a complex symbol for both Clokey and Pettibon, and his meanings are as malleable as the stretchy green man himself. The American Zen Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts, a friend of Clokey’s, thought Gumby’s signature head bulge was an ushnisha, or “bump of wisdom,” like those seen on Greco-Buddhist statuary. Pettibon’s friend, the artist Mike Kelley, thought it was a stylized depiction of Clokey’s overbearing father, who had a Ronald Reagan hairstyle. In Untitled (And I rise…), Gumby’s head bump stretches into the stratosphere, bleeding right off the top of the page. Is it a sign of his expanded consciousness, or has Gumby’s “refreshed ambition” gone to his head? Pettibon’s piece is playfully ambiguous.

In recent years, Pettibon has begun to employ deliberate misspellings as a formal device to interrupt our reading at the level of the word or even the phoneme. His air-themed piece, Untitled (Hoyt air…), features an image of a partly deflated Earth with a thinning atmosphere, along with the captions “HOYT AIR” and “HUBBELL TELESCOPE.” Clearly, the artist is concerned about the warming of our planet. But “HOYT” and “HUBBELL” are both misspellings (for “hot” and “Hubble”). It may be that Pettibon is alluding to Waite Hoyt and Carl Hubbell, New York baseball players from the 1920s. But the primary purpose of the extra letters, he says, is “to slow down the reading.” Climate change is an urgent crisis, but hearing environmental warnings too often can make us inured to them. By causing me to stumble over my own native tongue or search for hidden Duchampian puns in his words, Pettibon gets me to pay attention.

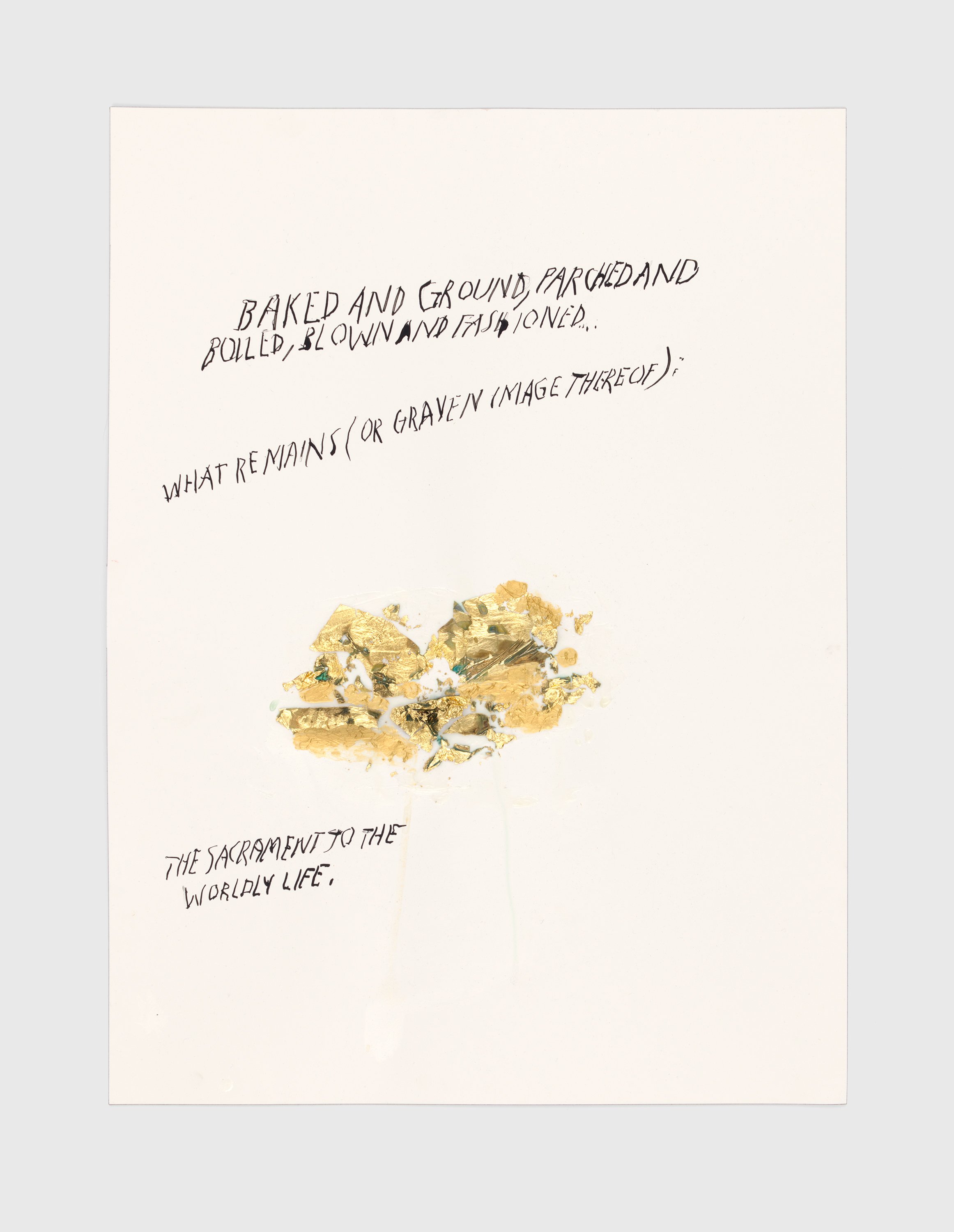

The fire-themed piece, Untitled (Baked and ground…), alludes to the biblical story of the Golden Calf, as well as to medieval alchemy. Instead of a painted image, Pettibon has adhered fragments of gold leaf to the surface of the paper. The text refers to a “graven image.” Dripping with excess adhesive sizing, Pettibon’s gold leaf has an entropic quality, like the leftover residue of a failed experiment. Medieval alchemy often went badly wrong, of course, and the Golden Calf of Exodus was ultimately destroyed. But Untitled (Baked and ground…) is not simply a cautionary tale. The Golden Calf was a symbol of artistic expression, and medieval alchemy, among other things, led to the development of oil paints. Artists risk failure every time they create, but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t keep trying. In this piece, Pettibon confronts artistic failure, as amplified by the relative instability of his materials. The final line of text at the bottom of the piece — "THE SACRAMENT TO THE WORLDLY LIFE,” — seems to imply that art is a secular rite whose meaning is bound up in the act of making, not the end result. Beautiful or not, it’s the sacrament of making that matters.

Pettibon’s use of religious language begs the question of what role religion and mysticism plays in his art. “I haven’t gone over to the side of mysticism or God or faith, personally,” Pettibon says. “That doesn’t mean I can’t relate to it as a subject in my work.” The artist cites the fourteenth-century mystical text The Cloud of Unknowing as one of his favorite books. “It borders on the kind of negation you see, at its most extreme, in [Kazimir] Malevich but especially in [Ad] Reinhardt.” If medieval mystics and modern abstract painters sought to purify themselves through negation, Pettibon negates their negation with works that are decidedly impure and polluted with cultural detritus. Still, he shares a sensibility with them, especially if we consider his method of decontextualizing and altering texts as akin to what Derrida called “writing under erasure,” where a writer crosses out words but still leaves them legible. Pettibon does not select his quotations simply to confirm or negate them, but rather to tease out their paradoxes, aporias, and internal ambiguities. “It’s [about] taking it seriously,” he says, “and sometimes putting yourself in the point of view of the author and of the reader at once.” He compares his method to how Charlie Parker built new songs from pre-existing chord progressions. In both cases, the goal is neither nostalgia nor satire but an ongoing and nuanced interchange with the cultural archive.

Pettibon’s work is full of speed bumps and red herrings but also moments of great candor and wisdom if we are willing to take our time and read between the lines.